Nepal: Magical Pokhara

Pokhara

A half-hour flight east in the morning had me disembarking and photographing my first impression of Pokhara’s blue, unpolluted skies with snow-capped mountains in the distance and unexpected tropical vegetation in the foreground. Had there been the same job offer there, I’d have accepted in an instant, so enchanted was I from the second I stepped off the plane. Many tours, and sites listing the twenty best things to do here, are easily found online, but this story and its images is about my time in Pokhara.

Below: Landing in Pokhara: strolling past Phewa Lake and turning right to find my hotel in a street with magnificent mountain views.

The scenic and peaceful Phewa Lake with its slender colourful row boats for hire, the charmingly decorated coffee shops and restaurants, the tropical vegetation set against dramatic white mountain peaks all work together to create a sort of ‘Shangri-La’ vibe. Domestic dwellings down streets running away from the lake are generally three storeys high, in a variety of designs but with an overall uniquely Nepalese geometric similarity. Gardens are well kept often with vegetable patches in the rear and lovely potted plants in the front. I did a lot of walking in Pokhara, enjoying the sunshine and interactions with friendly locals. In the main street, away from the lake, there are several bars with live music at night where I found it easy to strike up conversations with the young Nepalese crowd that spent their evenings there.

One thing that really left a lasting impression was all the cattle roaming the streets. My cab was stopped on three occasions because a cow was blocking the road. Then a bus driver had to honk his horn to get past a bull and cow mating in the middle of the street. At the liquor store, I virtually had to climb over a lovely tan-coloured cow having an afternoon siesta stretched out across the entrance. I asked, but no one seemed to know who they belonged to. In fact, they found my question odd. The cows just live there, eat whatever and sleep wherever their fancy takes them.

To explore farther afield, I opted for a full-day private sightseeing tour, one where I could decide the places I wanted to see. That was going to cost around AU$120, but when I told my hotel manager about my plan, he organised his nephew to take me instead at a substantial discount. The young man collected me at 4.30 am to see the glorious sunrise from Sarangkot – high in the mountains with a view across to Annapurna and its foothills, an area protected since 1986. For Trekkers, I’m told this region has good infrastructure meaning that along the way on 3- to 21-day treks, there plenty of tea houses for nourishment and guest houses for accommodation. Not tough enough for a long trek, I was even surprised by the mid-March sub-zero mountain air. Temperature differentials between valleys and mountains in Nepal are extreme and require smarter packing than what I’d brought! That morning, there were many tourists on a terrace huddled together in the dark before sunrise. Sitting on a collapsible chair, I was shivering so much that my driver gave me his jacket and raced off to find me some hot coffee. He seemed very keen to return a happy guest to his uncle’s hotel at the end of the day. Suddenly the sky brightened, and a ball of brilliant fire slowly rose from behind grey mountains. As it did so, the opposite mountain face lit up from grey to a brilliant, blinding gold sparking exclamations of “ah” and “wow” from the assembled crowd – humble witnesses, on this morning, to a daily event so significant that eons ago it kindled humankind’s belief in gods.

Below: The glorious sunset over the Himalayan Mountains (unfortunately, my images do not do justice to the experience).

After driving through small villages on the way back towards Pokhara, we made five stops: a Tibetan Settlement, the Ghurkha Museum, a Hindu temple, the Gupteshwor Mahadev Cave and the famous Peace Pagoda.

The Peace Pagoda is a Buddhist Stupa in brilliant white that has steps leading up to a broader mid-section from where one has a view of Pokhara and the Annapurna Mountain range. The golden Buddha statue has him in the posture he is said to have adopted when born. Most interesting to me was the scope of the endeavour to construct Peace Pagodas around the globe in the hope that the peoples of the world would live in peace. By 2000, eighty such Pagodas had been constructed in Asia, Europe and the USA. Most were inspired by – and constructed under the guidance of – a Japanese Buddhist Monk called Nichidatsu Fujii (1885-1985) who first had them built in Japan in Kumamoto, Hiroshima and Nagasaki to promote non-violence. He founded the Nipponzan-Myohoji Buddhist order, and it is Buddhist monks from this order who built the Peace Pagodas, including the Shanti Stupa, here in Pokhara.

The Gupteshwor Mahadev Cave is Nepal’s most famous cave and some say also its longest at 2950 metres. It consists of two chambers housing several Hindu shrines dedicated to Shiva and other deities. Both sections were open (the second is closed during heavy Monsoonal rains). After buying the ticket and warding off all the souvenir store vendors, the path leads to a dizzying spiral-shaped downward path painted in bright red that takes you to the caves. That unusual construction was worth the visit, but I was not motivated to enter. It was dark and slippery, and I’ve been in several more spectacular caves in other parts of the world. There’s a statue of the Hindu sacred cow which gives insight into why they roam so freely in Pokhara, where 82 per cent of the half million residents are Hindu (for whom cattle hold special significance), and 13 per cent are Buddhist.

At the Bindhyabasini temple, many women in gorgeous sarees passed by on their way to pray with friends and family.

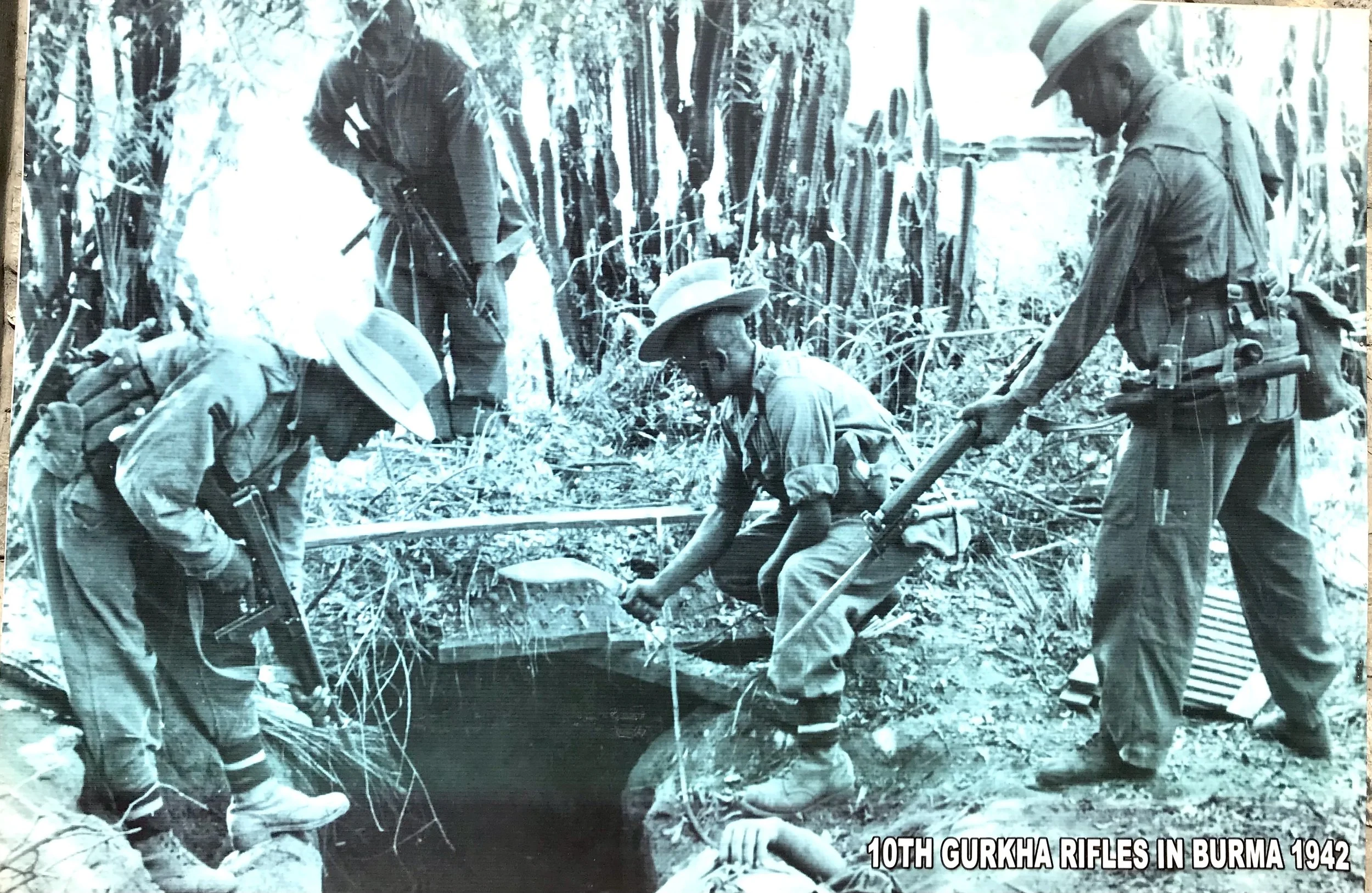

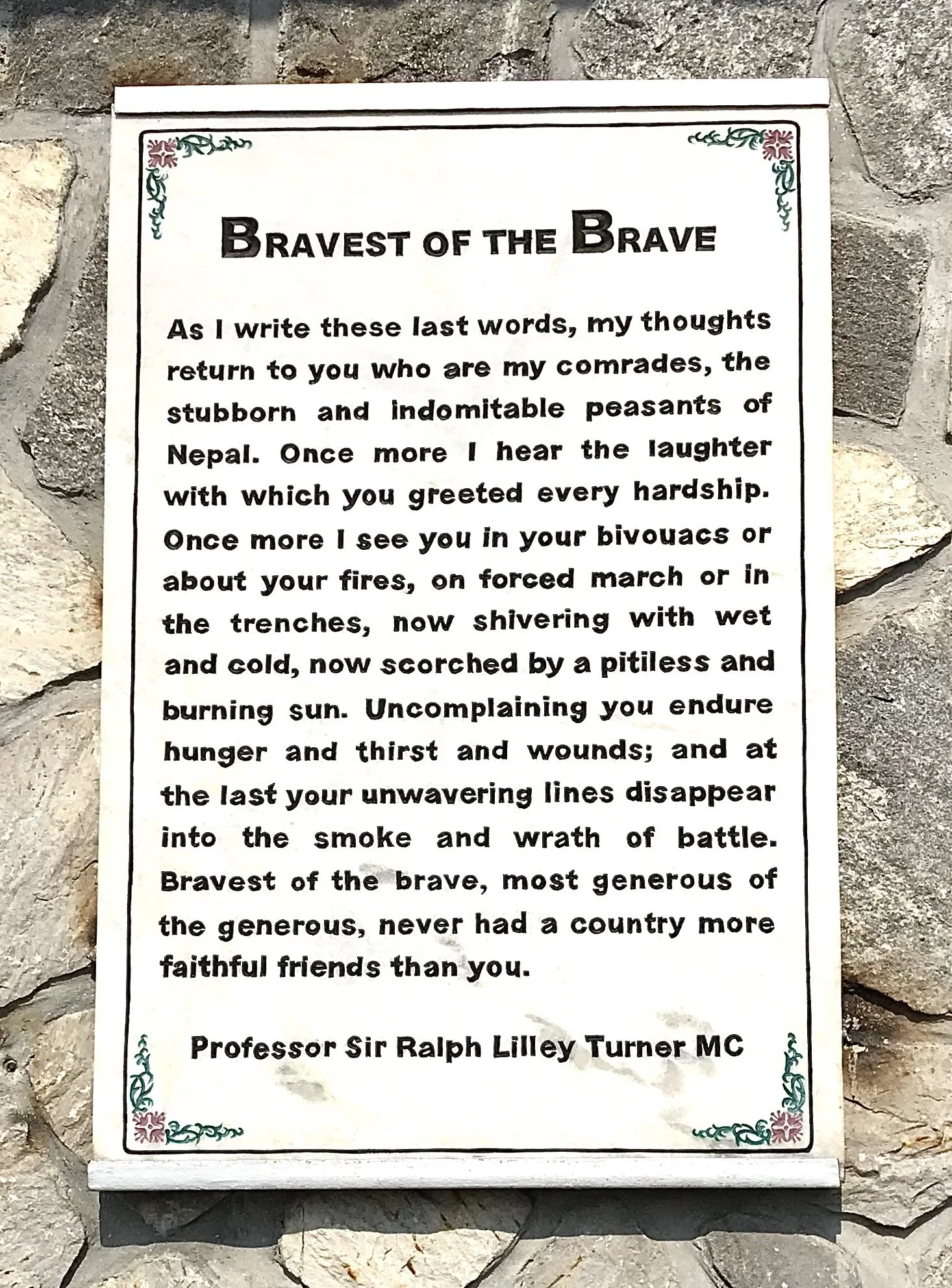

The Ghurkha Museum houses some wonderful B&W photographs that commemorate an era in which elite Nepalese soldiers, the Ghurkha, fought for the British Empire. The museum displays their uniforms, rifles, canons and equipment. It tells the world about the service they rendered to the British crown. A Ghurkha Museum in Britain also commemorates their bravery. They followed orders and fought for the British East India Company against those who wanted Independence for India. Today, they continue to be an important part of the British military, and in Nepal becoming a Ghurkha is a matter of great pride. Thousands apply but only a handful pass all the tests they are subjected to. If accepted, they face nine months of elite training in England. Afterwards, depending on their specific aptitude, they join a regiment in which they specialise. However, nowhere did I find evidence that they can reach the rank of officer. In recent times, highly trained Ghurkhas have been active in Iraq, Afghanistan, the Falklands and the Gulf Wars as well as taking an active part in peacekeeping forces deployed in places like Bosnia, East Timor and Kosovo.

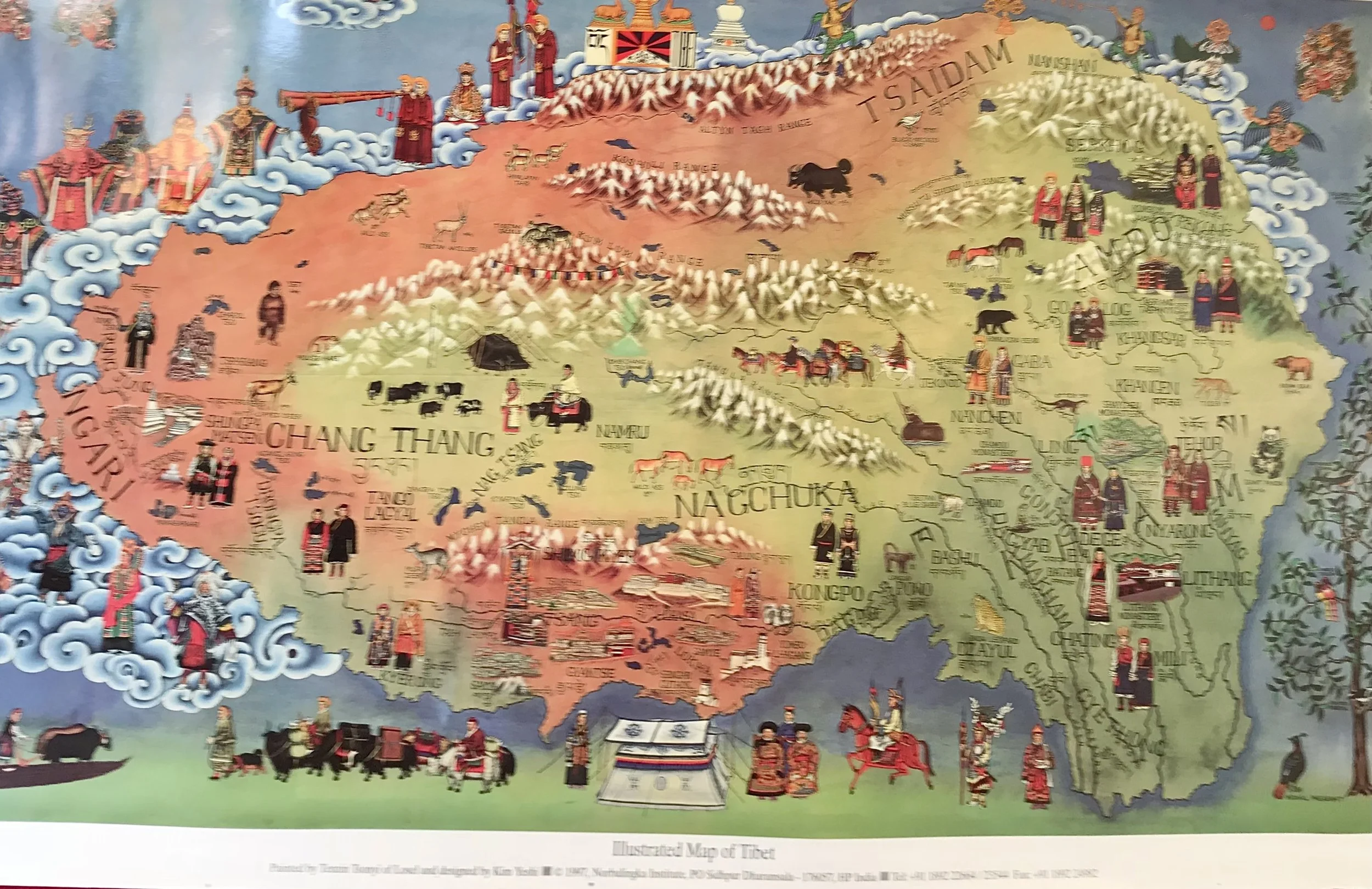

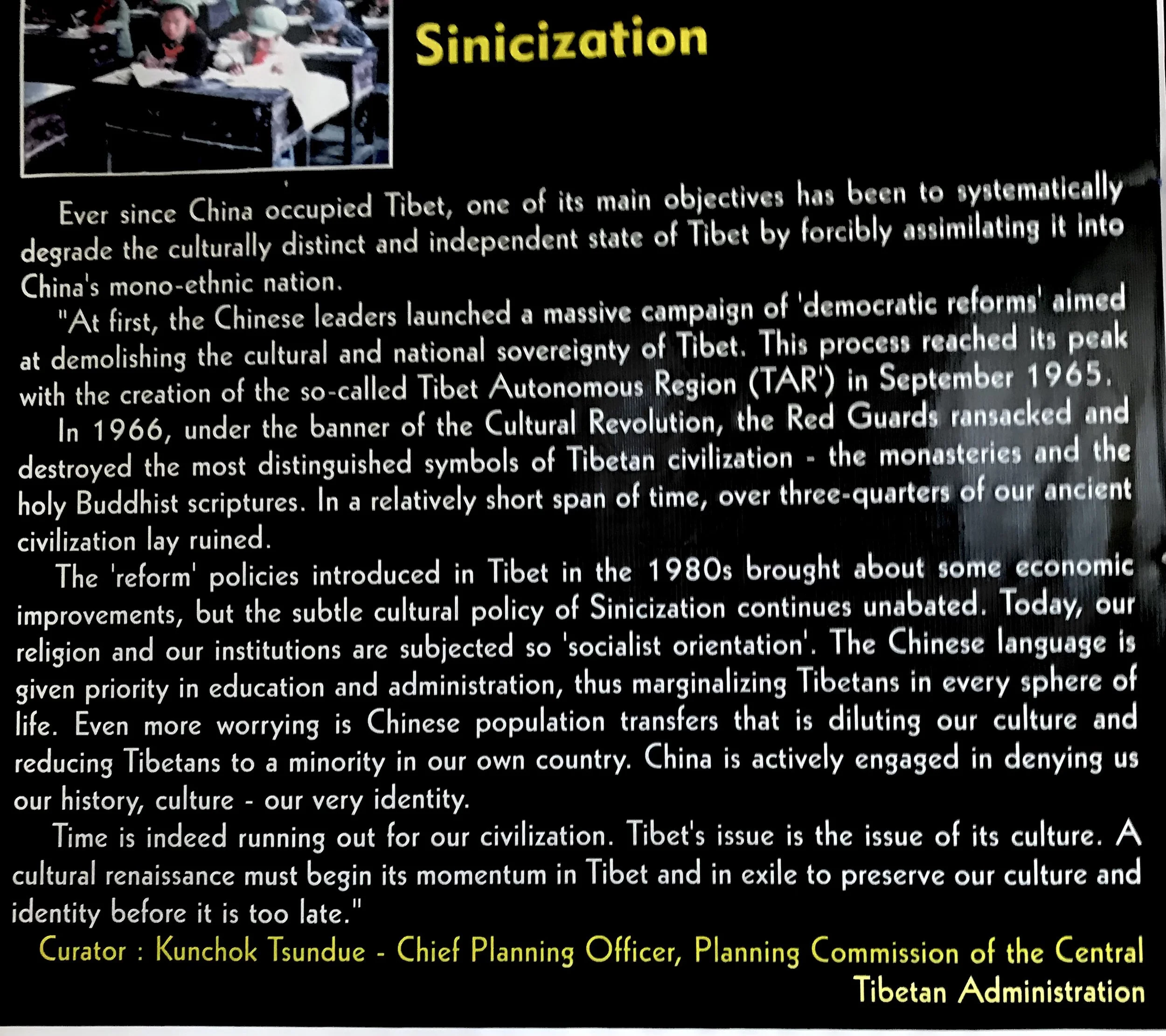

There are twelve official Tibetan settlement camps in Nepal, four of which are in Pokhara housing most of the thousands of Tibetans who live there. The Tashiling settlement I visited is one of these. It felt to me like the migrant hostel – army barracks in a previous life – that my family was sent to after arriving in Australia. Here there is a large hall for meetings and communal dining. At the museum, there are displays of Tibetan artifacts and photos with lots of texts that tell the story of the Tibetans’ escape from the Chinese forces that invaded their peaceful home high in the Himalayan Mountains. They began to settle here in 1962. Not much is held back in the description of those tragic events. Large signs break the story into chapters titled: 2000 years of Tibetan Independence before Chinese Occupation; Invasion (1950); Human Rights Violations (horrific personal accounts); Resistance; Sinicization (see example sign below); Escape, and The Journey to Nepal. At the centre of each of the four communities is a monastery. Some of the community’s income is derived from making souvenirs and selling traditional Tibetan food, but their main ‘industry’ is handmade carpet. Through the SOS Hermann Gmeiner School, the families at these settlements have access to primary and secondary schooling, creche and boarding facilities for students. The curriculum is taught in Tibetan, Nepalese and English. The younger generation, born in Nepal, goes out to work bridging the Tibetan and Nepalese cultures. The camp settlement where more can be learnt about Tibetan culture is Tashi Palkhel a little further from town and reachable by bus, cab or private driver. Interested visitors can learn about Tibet and its displaced people on a cultural tour though info@tibetanencounter.com

Other vehicle-based and trekking excursions from Pokhara that I’ve researched for my next trip that may be of interest are to the Langtang region and its National Park. The Sherpa people live here in rustic villages. They offer food and lodging. Meeting them in this way promises deeper insight into their culture. The scenery of the Langtang Region is reported to be spectacular and the many monasteries throughout make that a particularly rewarding experience. The two other large national parks: Chitwan National Park and Bardiya National Park can be reached from Pokhara, but the former is closer to Kathmandu, while Bardiya, with its 968 square kilometres that include beautiful canyon valleys, is closer to Pokhara. The park is home to Bengal tigers, rhinos, crocodiles and an abundance of bird life.